Thank you for having me here to speak today. It is a real pleasure to have this opportunity to discuss the economic outlook and the challenges that face the Federal Reserve in terms of monetary policy going forward. As always, my remarks reflect my own views and opinions and not necessarily those of the Federal Open Market Committee or the Federal Reserve System.

My assessment of where things stand today is mixed. On the positive side, the financial markets are performing better and the economy is now recovering. In fact, the improvement in financial conditions has caused usage of the Fed’s special liquidity facilities to fall considerably. Consistent with their design, these facilities have become relatively less attractive as market conditions have improved. Also, the Federal Reserve has begun to taper its rate of asset purchases. The Treasury purchase program will end this month and the agency mortgage-backed securities purchase program by the end of the first quarter of 2010.

On the negative side, the unemployment rate is much too high and it seems likely that the recovery will be less robust than desired. This means that the economy has significant excess slack and implies that we face meaningful downside risks to inflation over the next year or two. Also, there are those who express anxiety about whether the Fed has the tools and the will to raise the federal funds rate when the time is appropriate. I want to assure you that the Fed has the tools to tighten monetary policy regardless the size of its balance sheet. Moreover, we have the will to do so in order to keep inflation in check.

Turning first to the developments in financial markets, there is little doubt that we have seen a vast improvement over the past six months. The major equity indices have risen sharply, credit spreads have narrowed and bank equity prices have generally shown a substantial recovery. Many large financial and nonfinancial firms have found it relatively easy again to tap the debt and equity markets.

The recovery in financial asset prices has been mirrored—albeit with a lag—in the economy. Industrial production has begun to rebound as the pace of inventory liquidation has slowed. Housing prices and activity have recovered somewhat—aided by the improvement in housing affordability and the first-time homebuyer tax credit. Fiscal stimulus is providing support to consumption and to state and local infrastructure spending.

The vicious cycle we had a year ago—in which the deterioration in financial markets led to economic weakness and that weakness reinforced the tightening of financial conditions—has been broken. In fact, to some extent, it has been replaced with a virtuous cycle. As financial markets have recovered, that has led to an improvement in business and consumer sentiment that, in turn, has helped to lift the economy, spurring further gains in financial asset prices.

In the same way that the improvement in market conditions is helping to support a sustainable economic recovery, the fact that the recovery in economic activity is a world-wide phenomenon helps mitigate the risk of a so-called “double-dip.” The recovery in foreign demand should help to support the U.S. economy even if U.S. domestic demand grows more slowly than anticipated. Given these developments, the consensus forecast of about 3 percent annualized real GDP growth in the second half of the year appears reasonable.

However, I also suspect that the recovery will turn out to be moderate by historical standards. This is a disappointing outcome in that growth will likely not be strong enough to bring the unemployment rate—currently 9.8 percent —down quickly.

I see three major forces restraining the pace of this recovery. First, households are unlikely to have fully adjusted to the net wealth shock that has been generated by the housing price decline and the weakness in share prices. Peak to trough, home prices nationwide have declined by 11.5 percent measured by the FHFA (Federal Housing Finance Agency) index and by 32 percent according to the 20-city Case-Shiller index. With respect to stock prices, the S&P 500 index has recovered by more than 50 percent from the trough reached in March. But this should be put in context. The S&P 500 index is still about one-third below its recent peak in October 2007. Moreover, compared with its level ten years ago, the S&P 500 index is down by about 20 percent.

The shock to household net worth seems likely to have several important implications for household behavior. The shock creates a risk that the household saving rate could increase further. For example, during the period from 1990 to 1992, the household saving rate averaged about 7 percent of disposable personal income, considerably higher than the 4.3 percent average rate during the first half of this year. If the household saving rate were to rise, then consumption would rise more slowly than income, making it more difficult for the economy to develop strong forward momentum. In addition, it seems likely that some workers will respond to the wealth shock by postponing their retirement. This suggests that the labor force participation rate may rise once labor market conditions improve. This would tend to push up the unemployment rate, all else being equal.

The second force that could restrain the recovery is the fiscal outlook. The fiscal stimulus that is currently providing support to economic activity is temporary rather than permanent. This has to be the case if we are to ensure that fiscal policy is on a sustainable path over the long-run. This means that the positive impulse from fiscal stimulus will abate over the next year.

The third, and perhaps most important factor, is that the banking system has still not fully recovered. Bank credit losses lag the business cycle and are still climbing. Thus, while banks’ access to the capital markets has sharply improved, banks are still capital constrained and hesitant to expand their lending. Most importantly, some significant classes of borrowers—namely commercial real estate and small business—are almost wholly dependent on the banking sector for funds, and those funds are not easily forthcoming.

The commercial real estate sector is under particular pressure because the fundamentals of the sector have deteriorated sharply and because the sector is highly dependent upon bank lending. In terms of the fundamentals, there are two problems. First, the capitalization rate—the ratio of income to valuation—has climbed sharply. At the peak, capitalization rates for prime properties were in the range of 5 percent. That means that investors were willing to pay $20 for a $1 of income. Today, the capitalization rate appears to have risen to about 8 percent. That means that the same dollar of income is now capitalized as worth only $12.50. In other words, if income were stable, the value of the properties would have fallen by 37.5 percent. Second, the income generated by commercial real estate has generally been falling. For example, as the recession has pushed up the unemployment rate, the demand for office building space has declined; as the recession has led to a reduction in discretionary travel, hotel occupancy rates and room prices have declined; and as retail sales have weakened, this has reduced the demand for prime retail property space.

The decline in commercial real estate valuations has created a significant amount of “rollover risk” when commercial real estate loans and mortgages mature and need to be refinanced. The slump in valuations pushes up loan-to-value ratios. This makes lenders wary about extending new credit, even in the case when these loans are performing on a cash flow basis. This means that more pain likely lies ahead for this sector and for those banks with heavy commercial real estate exposures.

For small business borrowers, there are three problems. First, the fundamentals of their businesses have often deteriorated because of the length and severity of the recession—making many less creditworthy. Second, some sources of funding for small businesses—credit card borrowing and home equity loans—have dried up as banks have responded to rising credit losses in these areas by tightening credit standards. Third, small businesses have few alternative sources of funds. They are too small to borrow in the capital markets and the Small Business Administration programs are not large enough to accommodate more than a small fraction of the demand from this sector.

All of these factors will tend to inhibit the pace of the economic recovery. Given that the recovery is starting with an abnormally large amount of slack, and the pace of recovery is not likely to be robust, this means the economy is likely to have significant excess resources for some time to come. As a result, the balance of risks to inflation lies on the downside, not the upside, at least for the next year or two.

To see why this is the case, it is useful to note that inflation dynamics are mainly driven by two factors—the degree of capital and labor resource utilization relative to sustainable levels, and long-run inflation expectations. The degree of resource utilization is essentially driven by the business cycle and, and to some extent, by the Fed’s success in achieving the “maximum sustainable growth” component of its dual mandate. Inflation expectations, on the other hand, are driven by a combination of actual inflation outcomes and the credibility of the central bank’s commitment to price stability. If inflation is low and the central bank is credible, then long-run inflation expectations are likely to remain well anchored.

In practice, the relationship between the inflation rate and the level of resource utilization is very difficult to estimate accurately. This stems, in part, from the fact that the data on inflation and resource utilization are “noisy” and because sustainable levels of resource utilization are not directly observable. The fact that there is often not much resource slack in the economy also makes it hard to discern a clear empirical relationship.

Unfortunately, in this episode, we don't need a precise estimate of slack to be highly confident that the level of slack in the labor market is at or above the record of the post-World War II period. Although the headline unemployment rate of 9.8 percent is about one percentage point below its level at the end of the 1981-82 recession, other, more indicative measures paint a bleaker picture. For example, the prime age male unemployment rate is at a record high, by a significant margin. The labor market data released last Friday showed the September value at 10.4 percent, an increase of 6.5 percentage points from the start of the recession. In contrast, in the 1981-82 recession the prime age male unemployment rate peaked at 9.3 percent, rising by 4.2 percentage points from the start of that recession.

Over the post-World War II period as a whole, it was only in the wake of the 1981-82 and 1990-91 recessions that the prime age male unemployment rate remained above 6 percent for more than just a few months. In addition, during all post-war expansions, the prime age male unemployment rate has fallen below 5 percent, even during the short expansion of 1980-81. Currently, even under very optimistic forecasts for the economy, it appears very unlikely that the prime age male unemployment rate will dip below 6 percent before 2011.

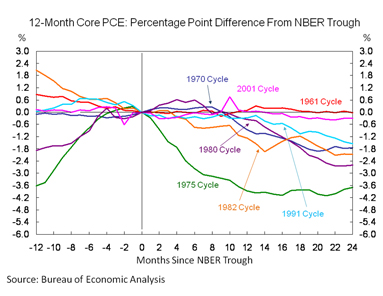

Alongside the current unusually high degree of labor market slack, we have a situation in which core inflation levels are low by historical standards. Continuing the comparison with the recession of 1981-82, it is worth noting that the core inflation rate today is almost 5 percentage points lower than it was toward the end of that episode. In addition, historical experience shows that the slack generated during a recession typically pushes core inflation lower in the early stages of recovery. So far, this cycle looks little different. As the degree of slack in the economy has climbed over the past year, measures of core inflation, particularly of core services inflation, have moderated. The tendency for service price movements to be persistent, coupled with the current unusually large amount of slack in the economy, suggests that the core inflation rate is more likely to fall than it is to rise over the next 12 to 18 months.

In summary, I believe the current balance of risks around the inflation outlook lie to the downside due to the very low level of resource utilization and the fact that long-run inflation expectations remain stable. This balance of risks is problematic because the current level of inflation is already so low—the core PCE (personal consumption expenditures) deflator has increased only 1.3 percent over the past 12 months. Thus, we would not need much of a decline in inflation to run the risk of an outright deflation. Outright deflation, in turn, would be a dangerous development because it would drive up real debt burdens and make it much more difficult for households and businesses to deleverage.

So what are the implications of all this for monetary policy?

The first implication is that the federal funds rate target is likely to remain exceptionally low for “an extended period.” The desired policy outcome is a robust recovery in the context of price stability.

The second implication is that the Federal Reserve needs to ensure that market participants and the public understand that the FOMC has the tools to exit smoothly from the very low federal funds rate, and that it stands ready to do so when the time comes. On this point, let me be perfectly clear: An enlarged balance sheet and the high level of excess reserves in the banking system will not delay or prevent a timely exit.

The angst about the Fed’s ability to exit smoothly stems from the rapid growth of its balance sheet over the past year. In September 2008, on the eve of Lehman Brothers’ failure, the consolidated Federal Reserve balance sheet was about $900 billion. Today it is about $2.15 trillion, and it is likely to peak at around $2.5 trillion early next year.

Some observers are concerned that this expansion will ultimately prove to be inflationary. Proponents of this view say that the monetary base, the broad monetary aggregates, and total credit outstanding have historically tended to move together with inflation, at least over longer time periods. Thus, if the monetary base is growing rapidly, as it has been over the past year with the growth in the Fed’s balance sheet, the argument is that this growth will ultimately lead to inflation.

This concern is not well founded because the Federal Reserve now has the ability to pay interest on excess reserves (IOER), and this tool allows us to prevent excess reserves from leading to excessive credit creation. It works as follows. Because the Federal Reserve is the safest of counterparties, the IOER rate effectively becomes the risk-free rate. By raising that rate, the Federal Reserve raises the cost of credit because banks will not lend at rates below the IOER when they can instead hold these excess reserves on deposit with the Fed. Because banks no longer seek to lend out their excess reserves, there is no increase in the amount of credit outstanding, no increase in economic activity and no risk that excessive credit creation will fuel an inflationary spiral.

In the event that the ability to pay interest on excess reserves for any reason proved insufficient or the excess reserves themselves had unanticipated side effects that the Fed wished to mitigate, we are developing a number of tools that can be used to drain reserves. Two such tools are large reverse repos with dealers and other investors and term deposit facilities for banks.

Finally, the Federal Reserve could always drain reserves the old-fashioned way, by selling assets. The vast bulk of the Fed’s portfolio is highly liquid—currently we hold $769 billion of Treasury securities, $692 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities, and $131 billion of agency debt against about $900 billion of excess reserves. All the excess reserves could be mopped up by asset sales alone if that proved necessary.

The Federal Reserve has been very aggressive in responding to the financial crisis. We have rolled out numerous new liquidity facilities and have engaged in lending activity under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act for the first time since the Great Depression. These actions have been successful in mitigating the risks of financial collapse and a more severe contraction in economic activity. The financial system is now healthier and the economy is recovering.

But despite these successes, we need to be clear that what has happened to our financial system and the economy is wholly unsatisfactory, and that a broad range of regulatory policies and practices need to be recalibrated to address the shortcomings of our financial system. With inflation low and long-run inflation expectations stable, and our ability to remove monetary accommodation in a timely manner intact, our near-term focus should be to keep significant monetary accommodation in place for an extended period in order to achieve our dual objectives of maximum employment and stable prices.

Thank you for your kind attention. I would be very happy to take a few questions.